Truman Capote: On His 100th Birthday, The Southern Literary Gadfly Still Gets Attention

- Nick Kossovan

- Entertainment

- Trending

- September 28, 2024

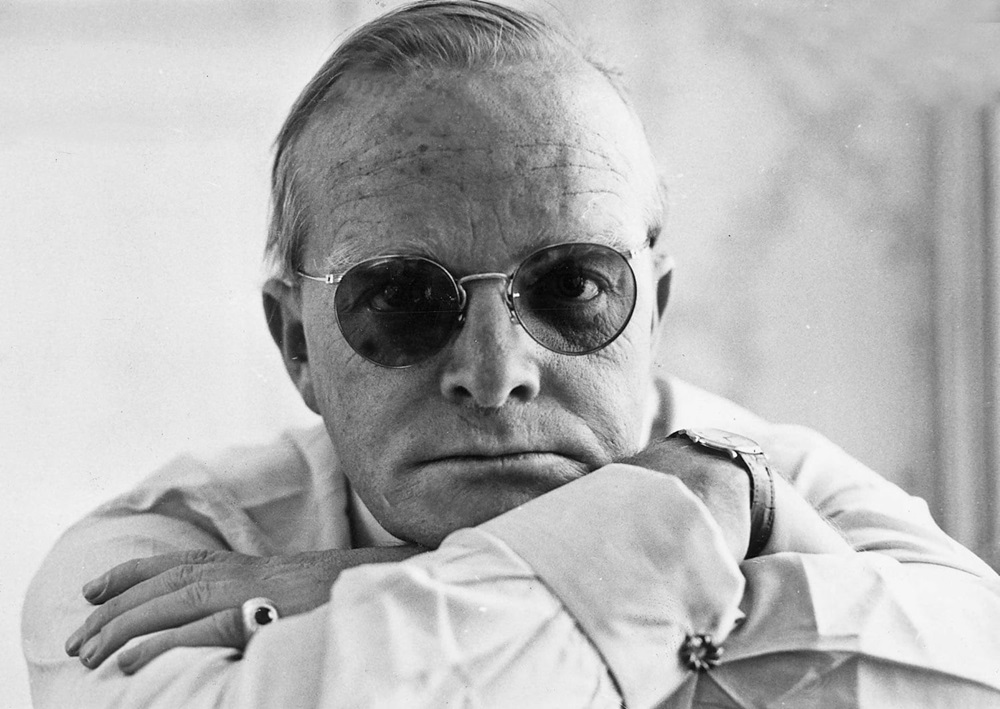

Image Credit, Truman Capote in 1968.Mirrorpix via Getty Images

Truman Capote’s influence on my writing makes it impossible to ignore his 100th birthday.

My journey with Truman Capote’s writing began when a high school reading assignment required me to read his short story, Children on Their Birthdays. I was captivated by Capote’s ability to use clear language to create vivid descriptions. The next day, I went to my local library and read his short story, A Christmas Memory (1956), about a particularly memorable Christmas spent with his older cousin, Sook Faulk, and checked out his true crime non-fiction novel In Cold Blood (1966), which I read over the weekend. Since then, I’ve devoured all of Capote’s published works and strive to write with as much clarity and emotional depth as he did.

Truman Capote is the bed on which I lay my writing.

Capote’s bookend dates:

- Born: September 30, 1924, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

- Died: August 25, 1984, Bel Air, Los Angeles, California, USA

Between these dates, Capote lived a life filled with destructive selfishness reminiscent of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s ‘all-out, full-tilt, hell-bent way of living.’ He could have been one of America’s greatest writers had it not been for two things: his need for celebrity, his own and surrounding himself with celebrities, and his alcoholism. While Capote did achieve the fame he desperately craved, it came, as it often does when one chases “to be loved and worshipped” at the cost of his humanity. Capote’s life serves as a cautionary tale about the danger of making a demonic bargain with your moral integrity to achieve celebrity status.

The American writer Dorothy Potter Snyder explained Truman Capote in three words, “great, gay and Southern.” Ironically, Truman’s first love wasn’t writing. Capote wrote in the preface to Music for Chameleons (1980): “Then one day I started writing, not knowing that I had chained myself for life to a noble but merciless master. When God hands you a gift, he also hands you a whip; and the whip is intended solely for self-flagellation.” Capote didn’t write for the sake of writing; it was a means to an end. First and foremost, Truman loved gossiping with “high society,” recognition, and the celebrity-like attention his writing provided.

Who doesn’t, at least to some degree, contort themselves to be loved, recognized, and accepted?

Capote wasn’t just a writer who offered immense literary value to American literature. Besides his ability to blend traditional Southern Gothic with modern sensibilities, Capote’s flamboyant nature unwittingly—due to the advent of television and its widespread reach, which he shamelessly exploited, even appearing in a comedy skit in 1973 on The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour—contributed to contemporary celebrity culture. Additionally, as far as I know, even though Capote avoided discussing his sexuality in interviews, he was one of the first openly gay celebrities in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, thanks to his ballsy “Like it or not, here I am!” attitude.

Capote matter-of-factly told anyone who inquired that his longtime companion was Jack Dunphy, a married man who left his wife for him and remained his companion until Capote sent himself into an early grave dying in Joanne Carson’s, the ex-wife of NBC’s Tonight Show host, Johnny Carson, Bel Air home having ruined his health and beautiful mind with alcohol and all sorts of recreational drugs. Gore Vidal, being “Gore Vidal,” declared Capote’s death “a wise career move.”

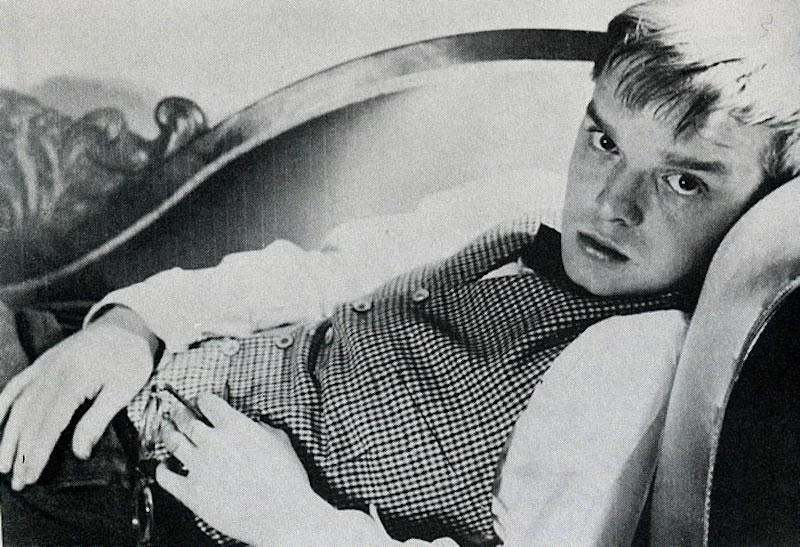

It was Capote’s ability to self-promote that helped him become so famous. On the back cover of his 1948 debut novel Other Voices, Other Rooms, a photograph of Capote, then 24, reclined across a Victorian couch in an overtly sexually suggestive pose generated quite a reaction among postwar conservative Americans. From the get-go, Capote knew how to create buzz and curate readers, as he did with his 1958 novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s, in which he captures the complexities of gender and sexual identity, so it resonated with a burgeoning audience longing for representation.

Capote’s most significant contribution to American literature and contemporary journalism was his groundbreaking book, In Cold Blood. Often regarded as the first nonfiction novel and the beginning of the New Journalism movement, In Cold Blood systematically recounts the events leading up to and following the unwarranted and violent murder during the early morning hours of November 15, 1959, of the Clutter family—Herb Clutter, his wife, Bonnie, and their teenage children Nancy and Kenyon—in Holcomb, Kansas. With vivid characterizations and psychological depth, Capote’s narrative style redefined narrative nonfiction and set the stage for future literary explorations of violence and morality.

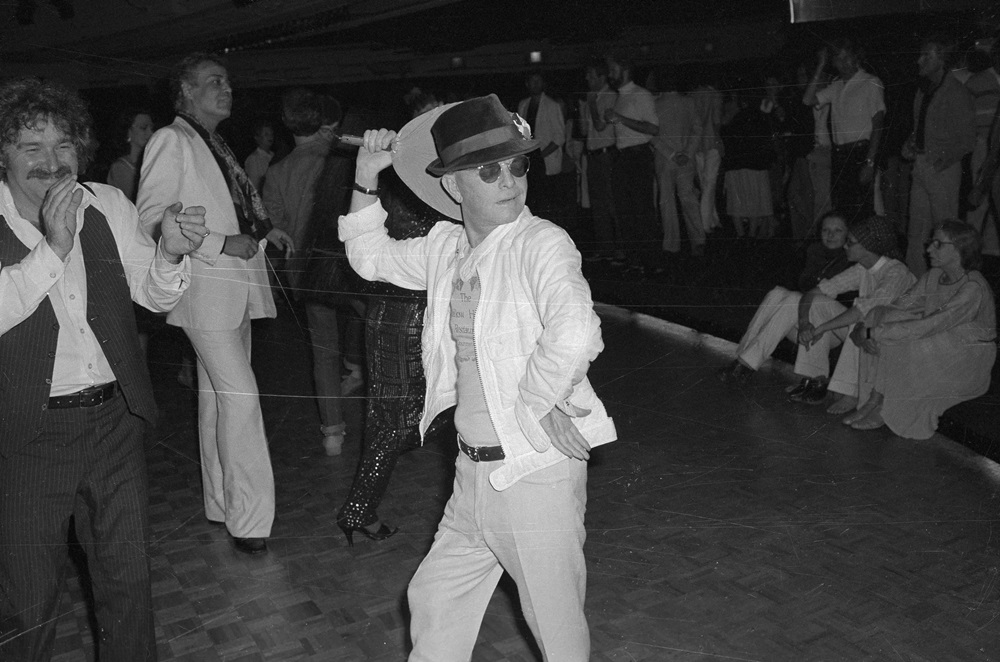

Capote’s dramatic flair extended beyond his writing. A regular at high-society gatherings, his social life was as vibrant as his prose. His ability to navigate different social strata and his keen observation of human behaviour lent credibility to his narratives. As a result, Capote emerged as a force in Southern Gothic literature, whose writing evolved into a more journalistic style while continuously challenging the social conventions and expectations of his time.

Capote’s impact on celebrity culture can’t be overstated. He was one of the first authors to seek out and wrap himself in the concept of celebrity author—a figure whose life and persona are as captivating as their work, not much different from Hemingway. Though he didn’t seek out fame, Papa led a life, possibly by design, that was, to say the least, compelling. Capote’s friendships and public “sharing” of their lives—essentially gossip—with celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe and socialites Lee Radziwill, Jackie Kennedy Onassis’ sister, and Babe Paley, wife of CBS founder William S. Paley, contributed to the creation of today’s celebrity culture.

Capote’s “Black and White Ball,” held at New York City’s Plaza Hotel on November 28, 1966, attended by some of the most prominent figures of the time, was a manifestation of his desire to merge artistic merit with social capital and served, as much of Capote’s life served, as a commentary on the transient nature of social status and fame.

If Truman Capote were alive today, with social media’s ability to create and destroy fame, I envision Capote would be constantly on the edge of his seat monitoring the digital circus, as most of us do.

Capote’s observations on celebrity culture were critical, often to the point of being scathing. His sharp wit and keen observations allowed him to dissect the absurdities of fame. His 1956 book, The Muses Are Heard, a journalistic account of The Everyman’s Opera’s mid-1950s cultural mission to the Soviet Union, reflects his fascination with the tensions between art and commerce and the commodification of personal identity.

Capote did not just participate in celebrity culture; he was the ubiquitous fly on the wall reporting on and critiquing the very world he inhabited, which ultimately led to his being shunned by those he vehemently wanted to identify with. Given Capote’s notorious self-serving nature, it’s hard to believe that no one he befriended didn’t consider his friendship came with conditions.

In keeping with the advice that writers should write about what they know, based on what has been published of Answered Prayers, his never finished tell-add novel, Capote packed, Answered Prayers, with thinly fictionalized versions of some of the world’s wealthiest and most fashionable women. Capote knew, as Marcel Proust and Oscar Wilde did, that stories which pulled back the curtain on a segment of society most people aren’t privy to would attract readers en masse. There wasn’t an affair, abortion, divorce or death among New York City’s elite that Capote didn’t know about. “Instead of a shrink, I had Truman,” said Marella Agnelli, Italian socialite, fashionista, and wife of Fiat chairman Gianni Agnelli.

Capote’s publicity skills failed him when he miscalculated (?) the possible consequences by publishing what was supposed to be Answered Prayers seventh chapter, La Côte Basque, in Esquire‘s November 1975 edition, exposing, along with heaps of dirty gossip and speculation, the private lives of New York City’s upper-class women. Overnight, Capote found himself on the outside, resulting in isolation and despair. Publishing La Côte Basque was a monumental act of self-destruction.

As a fair point of reference, Capote published the supposed first chapter of Answered Prayers, Mojave, in Esquire‘s June 1975 issue and received favourable reviews. La Côte Basque was too venomous to be ignored, and Capote was punished in a way that would ultimately destroy him; his access to the social elite he worked tirelessly to be a part of was revoked.

Capote’s contributions to American literature and his impact on celebrity culture are undeniable. As long as high school students are introduced to Truman Capote, and I hope they are, he’ll remain a vital talking point in our cultural conversations, and his writing, with its Southern charm and razor-sharp wit, will remain a staple of American literature.

As for me, I’ll continue to strive to paint with words, as Truman Capote seemed inherently able to do. However, more importantly, Capote’s life taught me this: It’s when you’re chasing a dream that you’re at your finest and always be careful as to what you do to get what you want.

Happy 100th birthday, Truman Capote!

______________________________________________________________

Nick Kossovan, a self-described connoisseur of human psychology, writes about what’s

on his mind from Toronto. You can follow Nick on Twitter and Instagram @NKossovan.