The World’s Readiness for a Pope from a Visible Minority: A Profound Shift in Catholic Identity

- TDS News

- D.O.C Supplements - Trending News

- Religion

- April 22, 2025

The election of a Roman pontiff stands as one of the most consequential spiritual events in global affairs, representing not just a change in leadership but a reflection of the Catholic Church’s evolving identity. As the world grows increasingly interconnected and diverse, a pressing question emerges: is global Catholicism prepared to embrace a pope who comes from a visible minority—whether Black, Asian, Indigenous, or even from a Muslim background? The implications of such a development would reverberate far beyond the Vatican walls, challenging centuries of tradition while presenting an unprecedented opportunity for the Church to fully embody its universal calling.

Historically, the papacy has been overwhelmingly European in its composition. Of the 266 popes recognized by the Catholic Church, only a handful have come from outside Western Europe. The last non-European pope before the modern era was Pope Gregory III in the 8th century, who was of Syrian descent. This Eurocentric tradition is not accidental but rather deeply rooted in the geopolitical and cultural realities of Christendom, where Rome served as both the spiritual and administrative heart of the faith for nearly two millennia. The structures of ecclesiastical power developed within this context, creating an implicit expectation that the Vicar of Christ would conform to a particular cultural and ethnic profile.

Yet the demographic reality of contemporary Catholicism tells a different story. The faith’s most vibrant and rapidly growing communities are now found in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia. Countries like Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Brazil, and the Philippines represent the new centers of Catholic vitality, while historically significant European dioceses face declining vocations and emptying pews. This shift has already begun to manifest in the College of Cardinals, where Pope Francis has appointed more prelates from the Global South than any of his predecessors. Cardinals like Ghana’s Peter Turkson, India’s Oswald Gracias, and Honduras’ Óscar Rodríguez Maradiaga have been frequently mentioned as potential papal candidates, signaling that the possibility of a non-European pope is no longer theoretical but increasingly plausible.

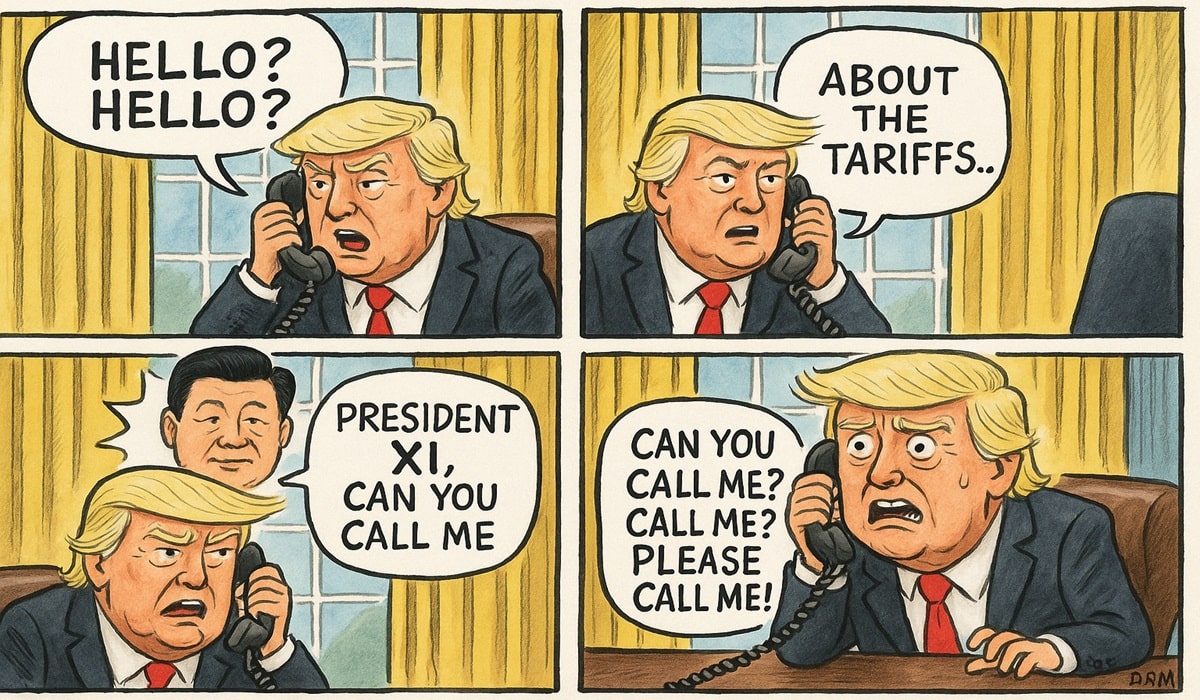

However, the barriers to such a historic development remain significant. Deep-seated cultural assumptions about spiritual authority and leadership continue to shape expectations, both within the Church hierarchy and among the laity. The image of the pope as an elderly white man in Renaissance-style vestments remains firmly entrenched in the popular imagination, reinforced by centuries of art, literature, and media representation. A pope from a visible minority would challenge these unconscious biases in profound ways, potentially facing resistance from those who equate European features with religious legitimacy.

Theological considerations also come into play. While Catholic doctrine emphasizes the universality of the Church, different cultural contexts have developed distinct approaches to spirituality, liturgy, and pastoral care. An African pope might bring greater emphasis on communal worship and oral tradition; an Asian pope could integrate more contemplative spiritual practices; an Indigenous pope from Latin America might prioritize ecological theology and liberationist perspectives. Such shifts could enrich the Church’s theological tapestry but might also unsettle those accustomed to a more Eurocentric expression of Catholicism.

Geopolitical factors further complicate the picture. The Vatican has long played a delicate balancing act in international relations, maintaining influence in Western power centers while ministering to a global flock. A pope from the developing world might redirect the Church’s focus toward issues like economic inequality, post-colonial reconciliation, or climate justice—potentially altering its relationship with Western governments and financial institutions. The election of a Latin American pope in 2013 with Francis was groundbreaking, but a pope from Africa or Asia would represent an even more dramatic reorientation of the Church’s center of gravity.

Despite these challenges, the momentum toward greater diversity appears inevitable. As the Catholic Church becomes increasingly non-Western in its demographic composition, the pressure for representative leadership will only grow stronger. The question is not whether a pope from a visible minority will emerge, but when—and how the Church and the world will respond.

The true measure of Catholicism’s universality will be revealed not in doctrinal statements but in its willingness to embrace a leader who breaks the mold of two millennia of tradition. When that day comes, it will test whether the Church can truly transcend its historical and cultural limitations to fully embody the radical inclusivity at the heart of the Gospel message.