The notion of a “jury of their peers” is a cornerstone of the criminal justice system, designed to ensure a fair and unbiased trial for defendants. The principle suggests jurors with similar characteristics or backgrounds should judge individuals facing charges against the accused. However, in reality, this concept is often far from being fully realized. Too frequently, cases are adjudicated without a diverse jury, leading to concerns about the influence of colour, race, ethnicity, age, education, and mental ability in jury selection.

The idea of a jury of their peers originates from the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution, guaranteeing the right to an impartial jury for all defendants. The underlying principle is that impartial peers who relate to their experiences and circumstances should judge individuals facing trial. Theoretically, this should foster understanding and empathy among jurors, leading to a more just and equitable verdict.

However, in practice, achieving this ideal has proven difficult. Jury selection often becomes contentious, with the prosecution and defence seeking jurors they believe will be sympathetic to their case. This process opens the door to the influence of biases, conscious or unconscious, which can compromise the notion of a fair and unbiased trial.

In the United States, jury selection is conducted through a process known as “voir dire,” where prospective jurors are questioned to assess their potential biases or prejudices. While the intention is to identify and remove individuals who may not be impartial, biases can persist throughout the process.

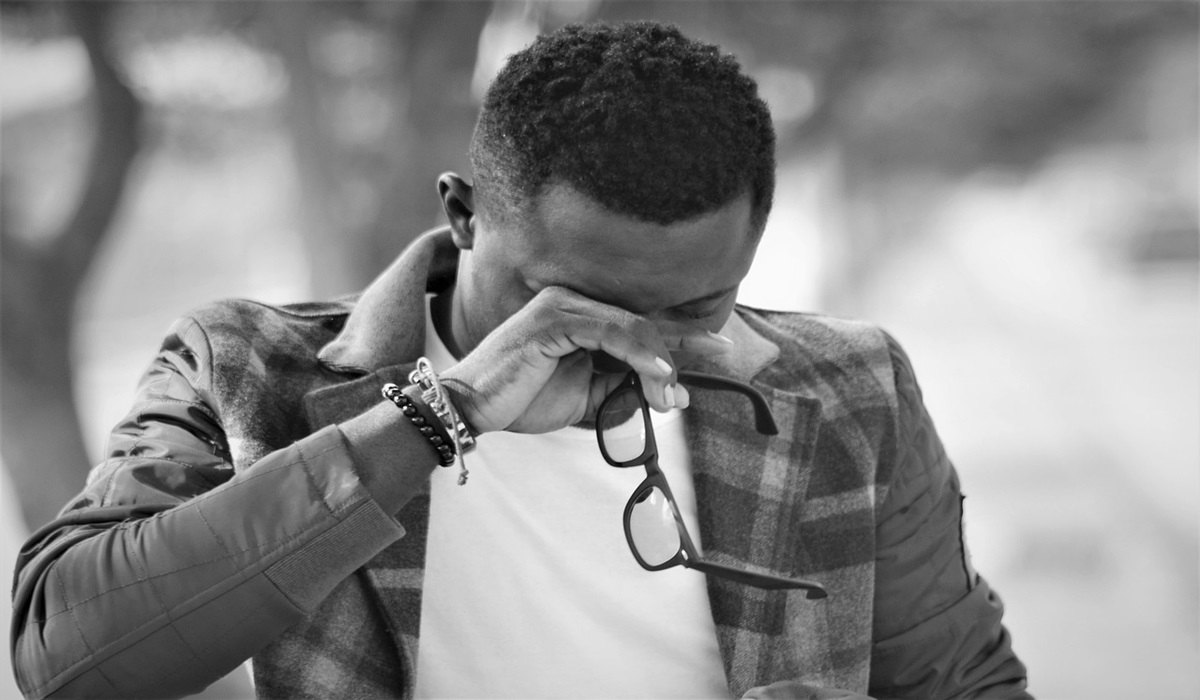

Colour, Race, and Ethnicity: Studies have shown that a jury’s racial composition can significantly impact trial outcomes. When defendants are from minority racial or ethnic backgrounds, their chances of receiving a fair trial can be affected if the jury pool lacks diversity. Instances of racial bias, both overt and subtle, can shape juror decisions and ultimately lead to unequal justice.

Age and Education: Differences in age and educational backgrounds among jurors can also affect trial dynamics. Younger or less-educated jurors might struggle to comprehend complex legal arguments, while older or highly-educated jurors may have biases rooted in their life experiences.

Mental Ability: Jurors’ mental ability, including cognitive impairments or disabilities, can also affect their ability to understand and weigh the evidence presented during the trial.

Defining what constitutes a “peer” is an intricate challenge. While the ideal suggests it should reflect shared life experiences and demographics, such as those mentioned earlier, objectively measuring and quantifying these factors is challenging.

One potential solution is to strive for greater diversity in jury pools. By ensuring a broader representation of various backgrounds, biases may be mitigated, and a more diverse range of perspectives can be brought to bear on the case. However, achieving this diversity may require systemic changes in jury selection and broader societal efforts to combat discrimination.

When cases are decided along racial, educational, or economic lines, it undermines the fundamental principle of a fair trial. Such outcomes perpetuate systemic inequalities and erode public trust in the justice system. In instances where it is evident that a jury does not represent the defendant’s peers adequately, declaring a mistrial could be considered. This option, however, is often fraught with legal complexities and does not necessarily address the root cause of the problem.

To move towards a more just system, there is a need to reimagine the measurement standard for equal trial justice. A holistic approach may include several strategies:

- Implicit Bias Training: Introduce mandatory implicit bias training for all participants in the criminal justice system, including judges, prosecutors, defence attorneys, and jurors. This training would aim to raise awareness of biases and promote fair decision-making.

- Expanded Voir Dire: Enhance the voir dire process to address biases and ensure a more diverse jury pool effectively.

- Community Involvement: Foster greater community involvement in the jury selection process to increase the representation of diverse backgrounds and perspectives.

- Technology Integration: Explore the responsible use of technology in jury selection, utilizing algorithms to minimize bias and increase diversity in jury pools.

The notion of a jury of their peers remains a noble ideal in the criminal justice system, but its realization faces significant challenges. Achieving true representation and equal justice requires a multifaceted approach, addressing biases at every level of the legal process. By embracing diversity and actively working to combat bias, we can move closer to a justice system that truly embodies fairness and equality for all. Only then can we uphold the promise of justice being truly blind.