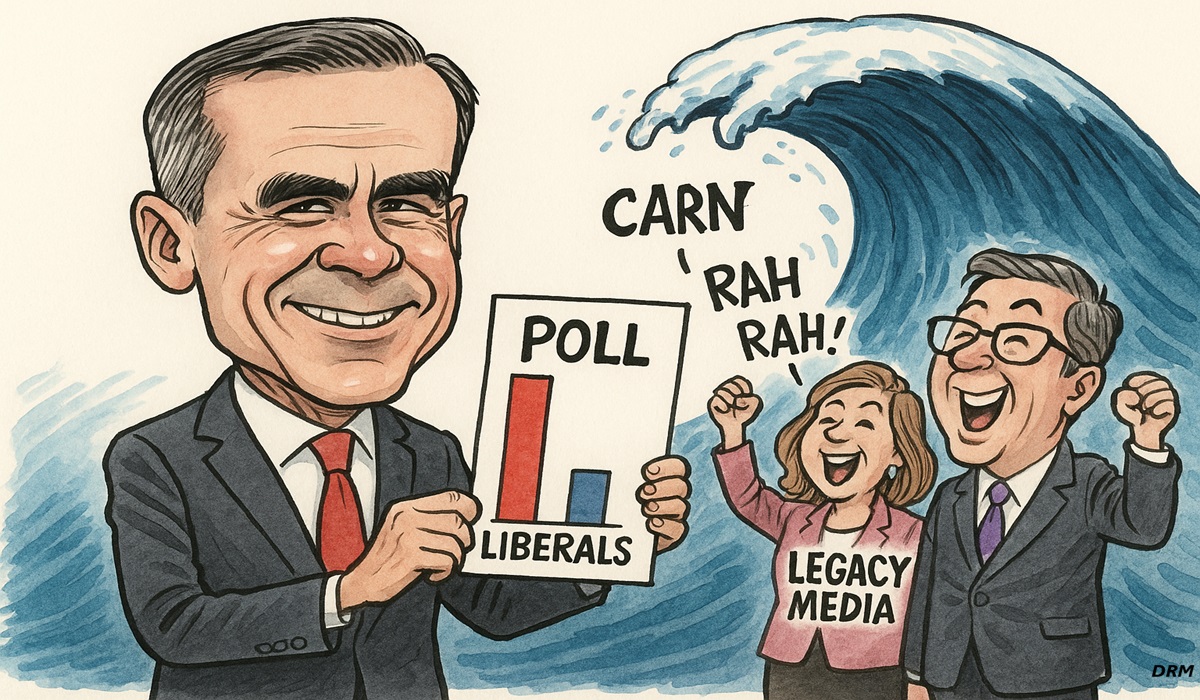

Mark Carney, Brookfield, and Bermuda: The $25 Billion Tax Question That Canada Keeps Dodging

- Kingston Bailey

- Business

- D.O.C Supplements - Trending News

- March 27, 2025

Image Credit, Arvid Olson

For all the political lip service paid to fairness, tax reform, and corporate responsibility, the Canadian tax system continues to serve as a doormat for multinational corporations. The latest example—Mark Carney, the former Bank of Canada governor turned Brookfield executive, reportedly benefiting from a structure that allows Brookfield Asset Management to route at least $25 billion in assets through Bermuda—should raise alarms not just about one man or one company, but about a fundamentally broken system that continues to reward financial engineering over national responsibility.

Carney, the current Prime Minister of Canada, now finds himself the face of a tax system that allows a Canadian-headquartered company to sidestep meaningful tax obligations at home. Brookfield, whose global reach includes energy, infrastructure, and real estate investments, has increasingly routed money through Bermuda—a jurisdiction that, while legal, is considered one of the world’s most notorious tax havens. And Carney, with his international credentials, is now tied to what critics call a glaring exploitation of international tax loopholes.

But let’s be clear: this is not about legality. It’s about morality, economic policy, and national interest. Brookfield isn’t alone. Countless Canadian companies, from mining conglomerates to tech firms, incorporate subsidiaries in the Cayman Islands, Switzerland, Luxembourg, or Singapore—places where corporate taxes are negligible or entirely absent. These structures, while technically compliant with Canadian law, drain the federal treasury and undercut the very premise of a fair society.

And the truth is, this isn’t a new problem. It’s structural. The Panama Papers were supposed to be the wake-up call nearly a decade ago. They exposed a sprawling global industry of tax avoidance and shell companies—many with Canadian links. What did Ottawa do? A few audits. A few headlines. No sweeping overhaul of tax laws. No new mandate for the Canada Revenue Agency to aggressively pursue high-level avoidance. And certainly no political courage to face the financial and legal juggernauts head-on.

Carney’s Brookfield ties put a spotlight on how easy it is for powerful corporations to keep their wealth offshore while enjoying all the benefits of doing business in Canada—stability, legal protections, infrastructure, educated workers. Why is it acceptable for these entities to contribute so little in return?

Even worse, the system punishes those who play by the rules. Canadian small businesses, which employ millions and can’t afford an army of accountants and lawyers to navigate offshore finance, are left paying full freight. Entrepreneurs and local manufacturers don’t get to route revenue through Bermuda. They file here. They pay here. They stay here. Meanwhile, the rich and well-connected create webs of subsidiaries across continents and call it “tax optimization.”

And it’s not just about Brookfield or Bermuda. Countries like the United Arab Emirates, particularly Dubai, are now heavily marketing themselves to global capital as low-tax havens with luxury perks. We’re entering a global arms race to the bottom—one where countries desperate for investment slash tax rates and regulatory protections just to keep corporations from bolting.

South of the border, Donald Trump flirted with the radical idea of eliminating corporate taxes altogether. That proposal was derided as unrealistic by many economists, but if it ever gained traction, it would rip the floor out from under Canada’s corporate tax base. Companies would flee. What’s left would be a hollowed-out shell of a tax system, relying even more heavily on individuals to fund public services.

So here’s the hard question: if a man as wealthy and connected as Mark Carney is part of a company that shifts billions offshore, what incentive does any Canadian corporation have to do the right thing?

If the system was functional, Carney wouldn’t need Bermuda. Brookfield wouldn’t need tax gymnastics. But the fact that they do—and still face zero consequences—tells you everything you need to know. There is no real will in Ottawa to fix the problem. Politicians talk about fairness, but when faced with the opportunity to implement global minimum tax rates, digital service taxes, or enforce transparency in corporate ownership, they balk. Too complex. Too controversial. Too politically risky.

So the charade continues. The CRA chases after waiters, gig workers, and freelance artists for minor tax infractions while letting billions leak through the cracks. Canada has become a country where tax justice is aspirational but not operational.

The question isn’t whether Carney did something illegal. It’s whether our country is being governed by people with the guts to look the system in the face and say: this isn’t working. And if they won’t say it now—after the Panama Papers, after Paradise Papers, after Brookfield’s Bermuda bonanza—when will they?

Because if we keep letting the ultra-rich siphon away public wealth with zero accountability, the next generation won’t just inherit a broken tax system. They’ll inherit a broken democracy.