One in three children who experienced repeated displacement in Iraq has developed a fear for their safety and trauma.

Ahmed Bayram,

Regional Media and Communications Adviser, NRC

Middle East Regional Office:

ahmed.bayram@nrc.no; +962 7 9016 0147

The new figures highlight the impact of protracted displacement for tens of thousands of Iraqis, years after military operations with the Islamic State (IS) ended. Over 100,000 people still live in informal sites, or makeshift shelters with minimal to no basic amenities, public services, or protection.

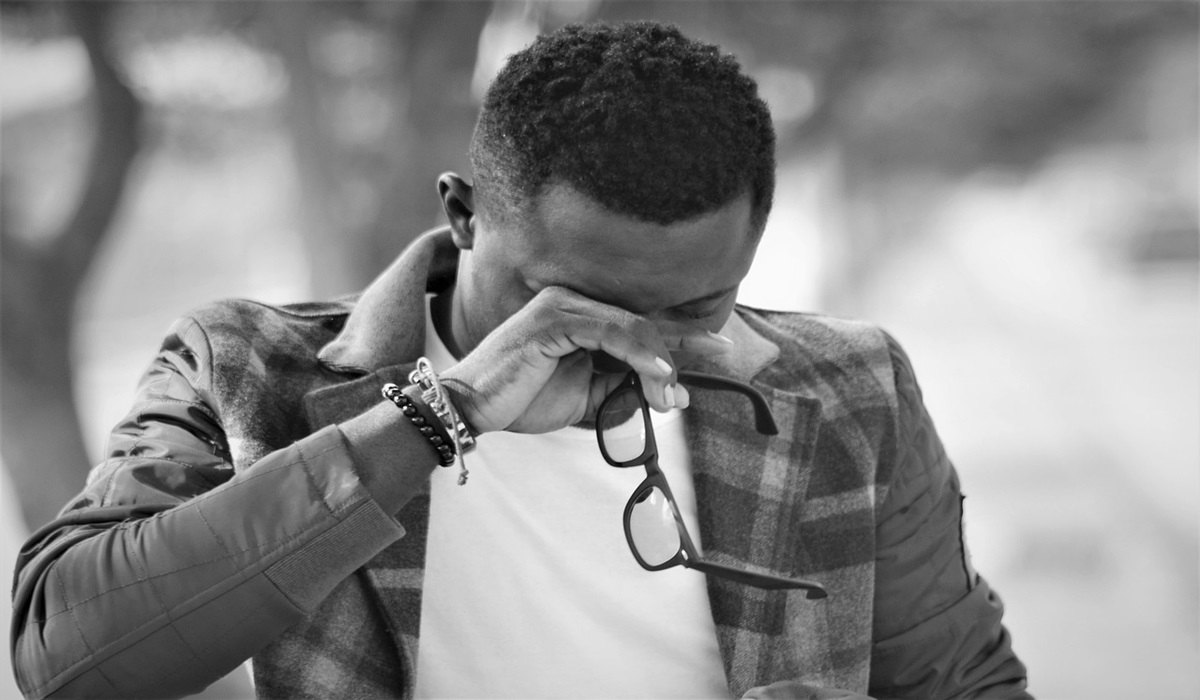

Children interviewed by NRC described how fear for their personal safety is a source of stress that has stopped them from leaving home or going to school. Past experiences of violence and repeated displacement have had detrimental consequences on their physical and psychological well-being and motivation to learn.

“Life is never normal for the tens of thousands of children who have not had a chance to settle with their families in one safe place,” said NRC’s Iraq Country Director James Munn. “Having to relocate multiple times means they are deprived of safety and education. They risk becoming forgotten.”

“More donor investment in mental health support and civil documentation is needed. This must take place while families are supported to improve their living conditions and acquire civil documents they urgently need,” added Munn.

Displaced female students are particularly at risk. Those interviewed recounted incidents of harassment in the community on their way to school that have derailed their safety and prevented them from continuing their studies.

“We have been away from our home, moving for years, until we relocated to these random shelters. There is nothing here; we had to take our children out of school and send them to work so we can survive. Sometimes what they earn is not enough for their commute. These are futures lost,” said Zahra, who was displaced with her children three times and now lives in Bzebez informal site in Fallujah district.

“Services are non-existent. You can’t see a doctor, and there is no drinking water. We have tried borrowing money and selling our mattresses and food for the cost of a doctor’s appointment. We want to go back home where we can work the land and send the children to school,” Zahra said.

NRC is urging donors, humanitarian and development actors to prioritize psychosocial support, teacher training, and school infrastructure in informal settlements. Further, NRC asks the Government of Iraq to work alongside partners to adapt reintegration services for children in informal settlements and streamline processes to acquire civil documentation for undocumented children.

NRC conducted more than 600 surveys in Anbar, Kirkuk, Ninewa, and Salah ad-Din governorates and found that two-thirds of out-of-school children in informal sites had to quit education because of a lack of access to online remote learning during the covid-19 pandemic. For those in school, 55 per cent studied in overcrowded classrooms. A similar number said their school had no bathroom facilities.

Secondary displacement refers to the voluntary or forcible displacement of internally displaced persons (IDPs) from their current location of displacement to another location where long-term recovery and integration are not achievable.

In early 2022, NRC carried out 615 household surveys and 38 key informant interviews (KIIs) to understand the needs of secondarily displaced children in informal settlements in Iraq. Children and their caregivers, teachers, community members, and government officials were surveyed and interviewed in Anbar, Kirkuk, Ninewa, and Salah ad-Din governorates.

Informal sites in Iraq have grown in number and size over the last three years, with 17,416 families dwelling in 477 informal sites across the country as of September 2021, according to OCHA. The estimated 103,000 people in informal settlements are often left outside the scope of humanitarian and government services.