Canada’s Relationship with China Should Be Made in Ottawa, Not Washington D.C.

- TDS News

- Canada

- March 23, 2025

Image Credit, Erich Westendarp

The decision to impose 100% tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles was framed as a defense of domestic industry. In reality, it was a political calculation — one that mimicked Washington’s protectionist stance without independent analysis or investigation. And now, the consequences are here: retaliatory tariffs from Beijing, rising diplomatic tension, and a missed opportunity to strengthen ties with the world’s second-largest economy.

Chinese Ambassador Wang Di didn’t mince words in his recent interview with The Globe and Mail. “Before imposing the tariffs on China, Canada did not do any investigation, and that was a blind following of other countries,” he said. That “other country” was unmistakably the United States.

The backlash from Beijing was not spontaneous. According to Wang, the tariffs imposed by Ottawa on Chinese steel, aluminum, and EVs were “unilateral, restrictive, and discriminatory,” violating international trade norms. China’s response, he emphasized, was “a countermeasure… targeted at the discriminatory measures taken.”

While trade spats often involve complex negotiations, the foundations of this dispute are surprisingly simple. There is no credible evidence that Chinese EVs are flooding the Canadian market. In fact, Ambassador Wang noted that his staff couldn’t even find one Chinese-made passenger EV on Canadian roads. The threat, in other words, is largely imagined — or imported from south of the border.

And that’s the core problem. Policy decisions affecting bilateral relations with Beijing are increasingly shaped not by domestic priorities, but by alignment with U.S. strategies. Ottawa didn’t launch its own review of dumping practices. It didn’t assess actual market impact. Instead, it echoed Washington’s rhetoric — a costly mistake for a country that claims to chart its own diplomatic course.

The move also contradicts past efforts to cultivate a balanced relationship with Beijing. For decades, this country was known as one of the few Western powers capable of maintaining productive ties with China without compromising core values. Those days feel increasingly distant.

Yet the opportunity to rebuild remains. “China is ready,” Wang said, urging a return to mutual respect, open dialogue, and pragmatic cooperation. He was clear that economic engagement doesn’t require full political alignment, but it does require trust — a commodity currently in short supply.

That trust has been further eroded by persistent barriers to Chinese investment, often framed under vague claims of national security. Wang cited BYD, one of the world’s top EV manufacturers, which considered opening operations here but walked away due to “huge difficulties, restrictions and obstruction.” Other companies, faced with the same obstacles, have chosen to invest elsewhere — and those benefits are now flowing into other economies, not this one.

The irony is that these investment opportunities align closely with domestic goals. Lower-cost, high-quality EVs could help meet ambitious climate targets. Strategic collaboration in energy, mining, and clean technology could strengthen critical supply chains. And yet, decision-makers continue to close doors in the name of risk aversion — or worse, to avoid upsetting Washington.

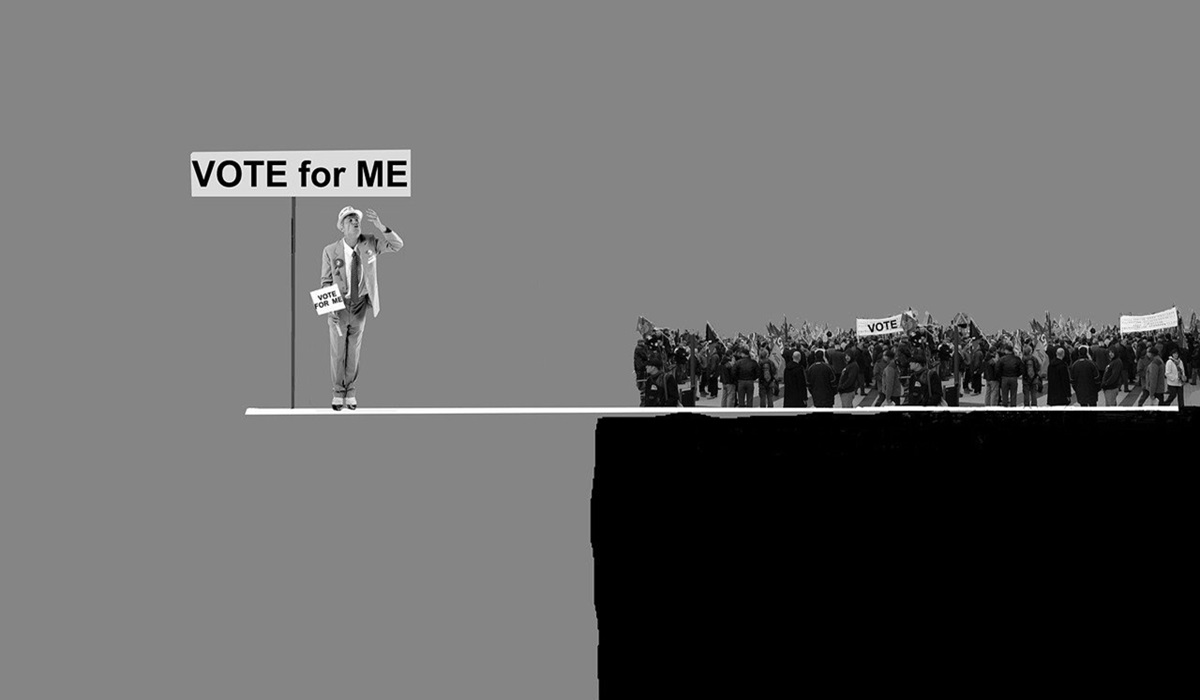

This isn’t just a trade issue. It’s a sovereignty issue. A country that lets another dictate its foreign and economic policy doesn’t act like a sovereign power. And at a time when the global order is shifting rapidly, playing follow-the-leader is a dangerous game.

Wang made it clear that Beijing isn’t asking Ottawa to choose sides. “The relationship between [your country] and the United States… has nothing to do with China,” he said. “But what we care about is that when Canada is growing its relations with other countries, it should not sacrifice China’s interests.” That’s not an unreasonable position — it’s a reminder that strategic independence doesn’t mean isolation; it means prioritizing domestic interests first.

What’s at stake isn’t abstract. It’s jobs, innovation, and access to some of the fastest-growing markets in the world. While American trade policy becomes more insular, nations across Europe and Asia are building deeper economic bridges with China. Meanwhile, Ottawa is pushing away investment, undermining trade, and straining diplomatic goodwill — for a fight that isn’t even its own.

Even on the issue of free trade, the contrast is stark. Negotiations between the two countries in 2017 and 2018 had promise, and Wang confirmed Beijing is still interested in pursuing a deal. “Of course,” he said, but warned that “political willingness” is the key ingredient — and so far, that willingness has been hard to find on this side of the Pacific.

In some sectors, the desire for collaboration is still strong. Wang pointed to Chinese energy firms working with domestic partners on LNG and shale projects. Crude oil exports to China have risen significantly. Yet continued restrictions and political signals of hostility are making companies think twice. “They do not know when the Canadian government will impose restrictions on the co-operation projects they are doing here,” Wang warned. “If that happens, their money would be going down the drain.”

There’s still time to change course. To do so, it does mean acting on principle, not pressure. It means evaluating evidence, not outsourcing judgment. It means remembering that trade is not a loyalty test — it’s a matter of strategy.

The bigger question is whether Ottawa wants to be a driver of its own future or a passenger in someone else’s vehicle. If the government truly believes in rules-based order, it should apply those rules consistently — including toward China. If it values economic diversification, it must stop shutting out the world’s largest emerging markets.

Ambassador Wang’s final message was simple: “Let’s work together and open a new chapter in our bilateral relations.” The choice now lies with this country’s leaders. Will they repeat the mistakes of alignment without scrutiny — or finally start thinking, acting, and negotiating on their own terms?

Time will tell. But one thing is clear: sovereignty begins with independent decisions. And that includes deciding how to engage with Beijing — not because Washington demands it, but because it serves the national interest.