Accountability in Bureaucratic Delays: The Case of 843 Main Street, Winnipeg

- TDS News

- Breaking News

- Western Canada

- July 4, 2024

In 2023, a major fire destroyed a building on Main Street and affected two adjacent structures. During his 2022 Mayoral election campaign, Scott Gillingham vowed to hold building owners accountable for removing the rubble after fires or abandoned buildings. However, this incident is not isolated; numerous buildings in Winnipeg are derelict or slated for demolition, raising broader questions about accountability.

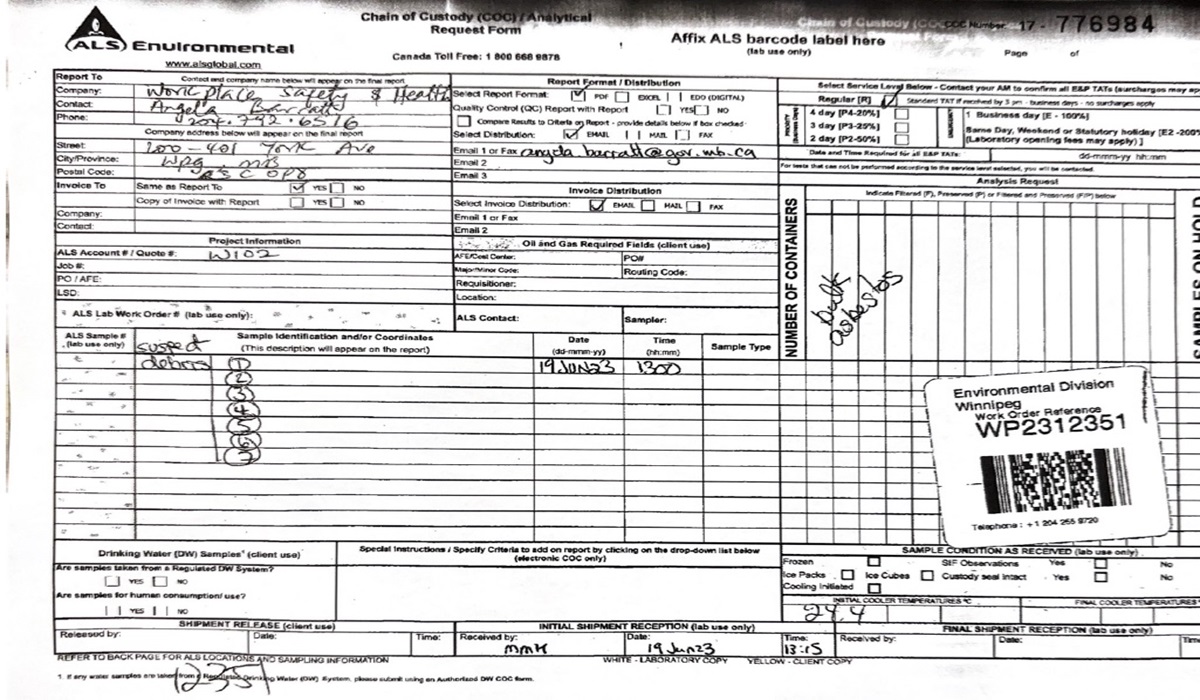

According to standard workplace health and safety policies, any building over a certain age that suffers a total loss due to fire may require testing for asbestos. Initial testing by the province indicated the presence of asbestos, but later, a Zoom call with the Department of Workplace Health and Safety (WHS) with the building owner uncovered an error: the results were mistakenly attributed to another building indicated by the building owner. Seeking clarity, the building owner hired a reputable demolition company to gather samples and turned them over to two reputable firms for independent testing. Out of 54 samples, 53 came back negative, with only one sample showing a minimal trace of chrysotile. However, the detection limit of the PLM method is >1%. Non-friable material with an asbestos concentration of <1% is considered not to contain asbestos, whereas friable material with an asbestos concentration of <0.1%. Despite this, WHS rejected these results and ordered new testing at the taxpayers’ expense to ALS Environmental. The building owner questioned this decision, especially considering the Work Place Health and Safety Occupational Hygienist Angela Barrett’s presence on-site without proper PPE, raising concerns about protocol adherence and draws into question if the building actually contain asbestos.

“Please be aware that the presence of asbestos has been confirmed and no amount of additional sampling will remove this status for the debris located on the site,” said Angela Barrett, WHS Occupational Hygienist in an email. In addition, she added in a separate correspondence, “I remain concerned about the wet demolition procedure where the airborne dust control measure is not applied near the point of debris disturbance.”

Manitoba Government, Workplace Health and Safety Occupational Hygienist Angela Barrett at the site alleged to have asbestos, without a hazmat suit or respirator.

“Safety and Health Officer Angela Barrett and myself, Safety and Health Officer Paul Martins, attended the site at 843 Main Street, Winnipeg. SHO Barrett and I are both competently trained occupational hygienists employed as Safety and Health Officers with Manitoba Workplace Safety and Health. After conducting a risk assessment of the environment, SHO Barrett and I accessed the premises from the rear of the building and took seven samples from the back room on the east side of the building. Photos showing the samples taken are attached.” Paul A. Martins, Occupational Hygienist Occupational Health Unit. Workplace Safety and Health

Knowing this vital information, why was the Occupational Hygienist on site without a respirator and hazmat suit, putting her health at risk? Furthermore, the demolition worker was observed in the excavator wearing a full hazmat suit talking with Barrett.

The financial implications for the building owner have been significant. Already facing over $100,000 in costs, the owner was informed by the city that failure to complete demolition and site clean-up by a set deadline would result in the city undertaking the remediation, potentially costing an additional $300,000. In addition, the building owner has stated he has sent multiple requests to the City of Winnipeg to forward an official invoice to him for them demolishing his building. To date, as per the building owner, none has been received. This means he cannot fulfill the insurance company’s requirement for reimbursement.

Samples Gathered by Workplace Health and Safety Occupational Hygienist Paul A. Martins

The owner’s attempts to extend permits faced extensive delays. A request was sent on May 6, 2024, to the Commercial Inspections Planning, Property, and Development department, and it took nearly 50 days to receive a response. In which the building owner had been given just over three weeks to have the rubble removed. However, extensions are done in six-month blocks up to three years.

This directive came despite a provincial stop-work order on the site, creating a confusing and financially draining situation. Why all the delays? Could it be that this is a revenue-generation tactic for the City of Winnipeg?

This delay highlights a recurring issue in Winnipeg’s bureaucratic processes. Moreover, when the province ordered new testing, only seven of the requested ten samples were submitted to ALS Environmental. Subsequently, the WHS indicated on the Zoom call they would be requesting ten samples from the building owner in which they provided 54, in comparison, WHS submitted seven. When the owner asked for these samples for independent verification, they had been destroyed by the laboratory as per the building owner.

Then there is another issue that ties into the rubble cleanup that contains potential asbestos. The proper disposal of this material is a critical health and safety issue. Allegations have emerged that asbestos materials once brought to city landfills like Prairie Green and Brady Road are not properly separated from regular garbage. This poses a significant risk to landfill workers and the public. Additionally, the mishandling of this dangerous substance could impede ongoing efforts to search landfills for the remains of missing Indigenous women, raising grave concerns about the city’s protocols.

This situation underscores the need for greater transparency and accountability in Winnipeg’s bureaucratic processes. Despite multiple attempts to seek answers from provincial and city officials, clear and direct responses were not provided or vague.

Fenced Debris at 843 Main Street, Currently under a work order stoppage by WHS

Several key questions remain unanswered. Is it standard practice for provincial employees from WHS to enter sites with alleged asbestos without proper PPE? What is the protocol for obtaining asbestos-related samples? What is the acceptable level of asbestos that would not require a wet demo? Why were the building owner’s independent test results not accepted by the province? How did the province mistakenly attribute incorrect test results to this property? What are the provincial policies for bulk gathering and transportation of samples? Why were the samples destroyed within a week, and what are the provincial guidelines for retention? Did anyone from WHS order the destruction of the samples? Did WHS follow all provincial protocols during this process? Why was the building owner’s offer to pay for additional testing declined? Can the City of Winnipeg override a provincial stop-work order?

The broader implications of this case extend beyond a single building, highlighting widespread issues with derelict properties in Winnipeg that face delays and bureaucratic hurdles. These inefficiencies and lack of transparency have far-reaching consequences for the community, including financial burdens on building owners, potential health risks from mishandled asbestos, and general frustration with bureaucratic delays. A strong call for accountability and transparency is essential. The provincial ombudsman must investigate the Department of Workplace Health and Safety and the city’s commercial inspections, planning, property, and development departments to uncover the reasons behind these persistent issues. Additionally, the ombudsman might shed light on why so many abandoned buildings remain uncleared and whether building owners across Winnipeg face similar tactics or issues with the city and WHS.

Former mayoral candidate Don Woodstock, who has been vocal about the alleged mishandling of asbestos at city landfills, brought these issues to light. “As an environmentalist, this is something quite troubling,” said Woodstock. “If it turns out there are irregularities that violate environmental laws, then there needs to be accountability.”

He also highlights his housing plan for the city of Winnipeg, which would have included a fast procedure for addressing the boarded and fire-ridden homes.

It is also evident, that the City of Winnipeg does not have the authority to overrule the province on a Stop Work order, but there is a workaround when it comes to asbestos debris removal. The City can issue a tender requesting a Wet Demo permit if the building has confirmed asbestos which would allow contractors to come in and do the work.

This is a stark reminder that accountability is not just a buzzword; it is a fundamental principle of good governance. Building owners and taxpayers should not bear the brunt of bureaucratic inefficiencies and mistakes. The city and provincial authorities must be held to account for their actions and decisions. Transparency must be more than a promise; it must be a practice that ensures public trust and confidence in the institutions that serve them.

This case is a call to action for all stakeholders involved. The unanswered questions must be addressed, the bureaucratic processes must be streamlined, and the financial and health risks must be mitigated. Only through accountability and transparency can the city of Winnipeg and the Department of WHS restore public trust and ensure that such issues do not continue to plague its residents. The time for action is now, and the responsibility lies with those in power to make the necessary changes.

Chain of Custody request form submitted by Workplace Health and Safety Occupational Hygienist Angela Barrett

We reached out to the Manitoba Minister of Labour Malaya Marcelino and the Department of Workplace Health and Safety and they did not provide a response. We are also still waiting on a response from The Prairie Green landfill.

With respect to the Brady Landfill, the City of Winnipeg responded by emphasizing that they follow strict protocols for asbestos disposal. Specifically, “At Brady, asbestos disposal is by appointment only. Haulers must arrange for disposal in advance and provide details on the hauler, generator, quantity and source of asbestos. Brady landfill only accepts asbestos on Wednesdays, and it must be wrapped/bagged in 12-min polyethylene.” Upon arrival, the asbestos is carefully managed to prevent contamination and ensure safety, including immediate covering with waste and recording GPS locations for all disposals.

The City of Winnipeg also stated they intervened in September 2023 to perform an emergency demolition at 843 Main Street due to safety concerns, but the remaining cleanup is the property owner’s responsibility. Furthermore, another city spokesperson Kalen Qually indicated they communicated promptly with the owner regarding the clean up. If they truly believe waiting almost 50 days to respond to business owners is in a “timely” manner, what does this say about efficiency and how taxpayer dollars are being spent?

We reached out to Crisp Analytical, one of the laboratories that conducted the testing, and they said they are regulated by The National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program (NVLAP), and are required to retain samples from testing on file for at least 30-90 days, especially when it is for asbestos. We reached out to ALS Environmental by email and phone to comment on the building owners allegations, but we did not receive a response.

It is crucial to note that the Provincial Bureau protocol hurdles began under the previous administration. The province should address this issue and be prudent to remove the stop work order because it looks like it could be a potentially costly endeavor for the province to continue if it ends up in court. There definitely seem to be some protocol answers that need to be addressed with the WHS internally and how they handle matters going forward. Ultimately, it is the Manitoba tax payers who will once again be left holding the bag for decisions made by the City and Provincial governments.