The Myth of Progress: Why Government Efficiency Remains a Global Embarrassment

- TDS News

- D.O.C Supplements - Trending News

- April 16, 2025

In a world where we’ve mastered the art of instant communication, mapped the human genome, and now send billionaires joyriding into space, it’s a damn mystery why governments still take years—sometimes decades—to pass meaningful legislation. We live in a time when artificial intelligence can write novels, skyscrapers can be built in 24 hours in parts of Asia, and data can be transferred across the world in milliseconds, yet we still wait entire election cycles for basic infrastructure repairs or policy changes that should’ve been resolved generations ago.

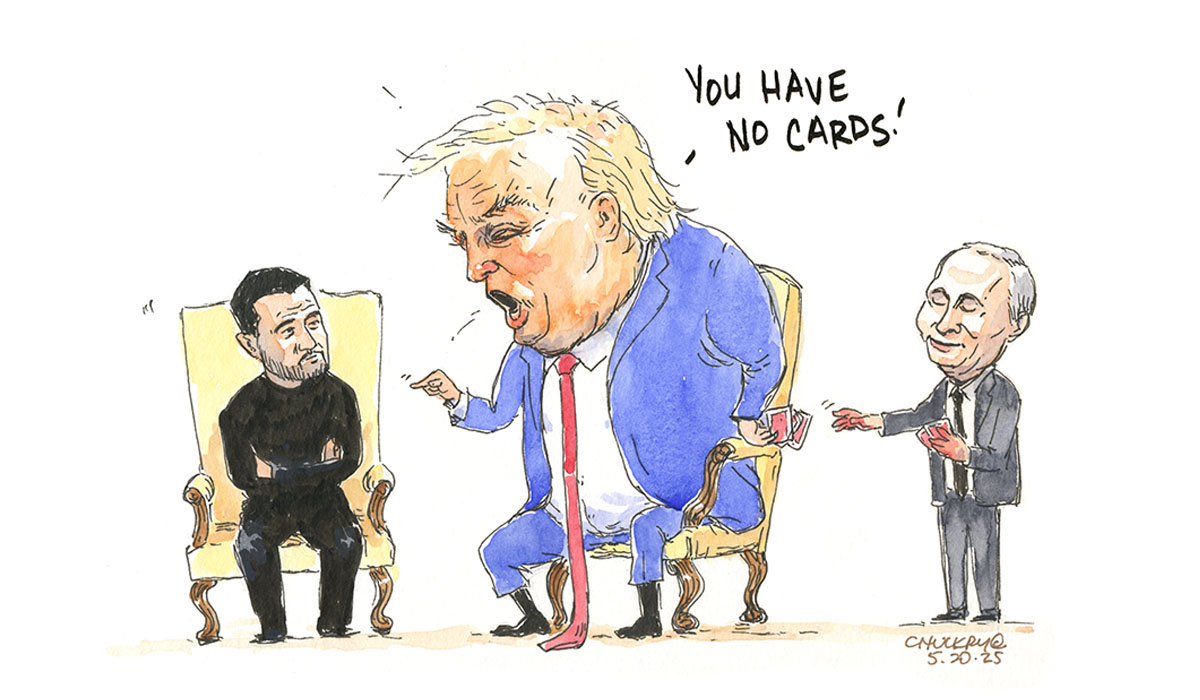

Let’s call it what it is: inefficiency wrapped in red tape, smothered by ego, and served with a side of political theater.

For centuries—yes, centuries—we’ve had governance. We’ve had councils, parliaments, congresses, senates, and cabinets filled with people who are, if nothing else, surrounded by intelligence. Whether through merit, nepotism, or the sheer weight of money, most of these people have access to experts, researchers, civil servants, and data that could solve most problems in short order. But somehow, nothing ever moves quickly. Why?

Compare the so-called “developed world” to countries often dismissed as “developing” or “emerging.” In Malaysia, it’s possible to secure a residency visa in two hours. In parts of Canada, it takes an entire summer to repave a city block. In Winnipeg, a single-family home might take a year to construct, while in China, a 10-story building can rise in less than a week. These aren’t hypotheticals. They’re not exaggerations. They’re hard truths that should raise eyebrows and ignite outrage.

Governments in places like Dubai and Singapore don’t claim to be the best at everything—they aim to find the best, wherever that may be. They borrow policies, processes, and technologies from around the world without the arrogance of insisting their own way is the only way. That humility is what fosters true innovation. Meanwhile, Canada and the United States continue to act as though they’re too advanced to learn anything new, all while their infrastructure crumbles, their healthcare systems buckle, and homelessness surges to levels that rival regions hit by war or disaster.

The United States—still clinging to the myth of exceptionalism—has nearly 50 million people without health insurance and leads the world in mass shootings. Canada, paralyzed by bureaucracy and provincial-federal finger-pointing, watches its housing crisis explode while families are forced to live in tent cities. These are not problems exclusive to democracies, autocracies, or any particular governance style. These are the signs of systemic rot—where good ideas die in committee, urgency is lost in partisanship, and accountability is a campaign slogan, not a principle.

So, what gives? The truth is, we’ve confused complexity with competence. We’ve mistaken long debates for deep thinking. We’ve allowed leaders to throw around words like “world-class,” “top-tier,” and “best-in-the-world” while delivering bottom-of-the-barrel outcomes. Why? Because it sells. Because it keeps the machinery of politics humming. Because voters, for too long, have rewarded rhetoric over results.

We have centuries of human history, data, and experience. We have seen what works—from housing policies in Vienna to transit systems in Tokyo to digital government platforms in Estonia. Yet we still build our systems on legacy frameworks designed before the internet, before globalization, before climate change became a ticking bomb. The inefficiencies aren’t accidental—they are structural. Built into the bones of our democracies are endless layers of approval, review, consultation, and political posturing. And it’s killing us—literally.

Look around. Poverty isn’t disappearing—it’s mutating. Chaos isn’t fading—it’s becoming normalized. Death, destruction, war, famine—these are no longer exceptions in the news cycle. They are the cycle. And still, we pass laws at the speed of molasses.

We have the knowledge. We have the tools. What we lack is courage. Political courage. Moral courage. The will to stand up and say: this system is broken and it’s time to fix it—not patch it, not tweak it, but transform it. That starts with governance that values outcomes over optics, timelines over talking points, and leadership over legacy.

The world doesn’t need more promises. It needs policies that work. We don’t need more symbolic gestures. We need radical action. Because if civilization, after all this time, still can’t get the basics right—then maybe the real crisis isn’t politics or poverty, but our refusal to evolve.

And if that doesn’t change, then maybe we don’t deserve to call ourselves a modern society at all.