Image Credit, Glen Kelp

In the hallowed halls of government, where presidents, prime ministers, ministers, and secretaries come and go with the rhythm of elections and political cycles, there exists a less visible, but profoundly influential, force: the bureaucratic machinery. This entity, composed of long-serving civil servants and obscure power brokers, often determines the direction of policy and the functioning of government far more than the elected officials who nominally hold power.

Unlike elected officials, who may serve terms as short as a few years, the employees within the bureaucracies of Western governments often spend decades in their positions. These civil servants possess an in-depth understanding of the intricate workings of government, institutional memory, and established relationships that allow them to navigate the complexities of policy and administration with unmatched expertise. This stability provides continuity and a safeguard against the caprices of changing political leadership, but it also poses significant challenges to enacting swift or radical change.

The notion of a “deep state”—a shadowy, unelected cadre of officials and influencers who control the levers of power—has gained traction in political discourse. While often associated with conspiracy theories, there is a kernel of truth to the idea that beyond the elected officials, a network of advisors, lobbyists, and long-serving civil servants wields substantial influence. These individuals, who come with metaphorical briefcases filled with knowledge and connections, guide the decision-making processes and ensure that policies align with established norms and interests.

In modern democracies, the influence of lobbyists and special interest groups cannot be overstated. These actors play a critical role in shaping legislation and policy by providing expertise, campaign funding, and strategic advice to politicians. The reliance on these groups creates a symbiotic relationship where elected officials, in exchange for support, often champion the causes and interests of their benefactors.

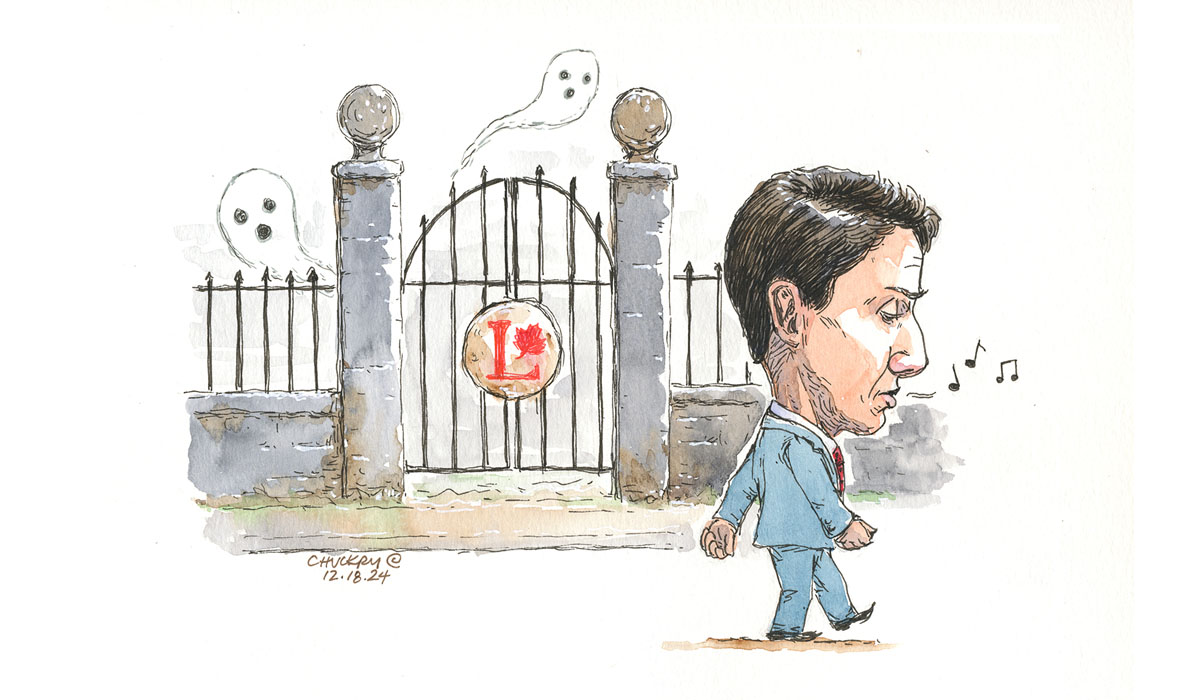

Given this landscape, enacting meaningful change becomes a herculean task. Newly elected officials, despite their mandates and electoral promises, quickly find themselves ensnared in a web of entrenched interests and bureaucratic inertia. The need for continuity and stability often necessitates compromise and incrementalism rather than bold reforms. Moreover, the procedural complexities and institutional resistance within the bureaucracy further stymie efforts to implement sweeping changes.

Institutional memory, while invaluable for maintaining continuity, can also act as a barrier to innovation. Long-serving civil servants are the custodians of this memory, ensuring that policies and practices are informed by historical context and past experiences. However, this same memory can lead to a preference for the status quo and a reluctance to embrace new ideas or untested approaches.

Behind the scenes, beyond the realm of public scrutiny, are the power brokers who significantly influence the political landscape. These individuals and entities—ranging from corporate executives and financial donors to think tanks and policy advisors—play a pivotal role in shaping the priorities and actions of elected officials. Their influence is often exerted through financial contributions, strategic counsel, and access to networks of power and information.

In this context, the question arises: is true democracy attainable when so much power lies outside the hands of the electorate? The intricate dance between elected officials and the permanent bureaucracy, coupled with the influence of unseen power brokers, raises concerns about the efficacy of democratic governance. The ideal of democracy rests on the notion that elected representatives reflect the will of the people, but the reality is often more complex and less transparent.

One of the most significant factors undermining democratic ideals is the role of campaign financing. Political campaigns, especially in countries like the United States, require vast sums of money, leading candidates to seek funding from wealthy individuals, corporations, and special interest groups. This financial dependence creates an environment where policy decisions are heavily influenced by the interests of donors rather than the broader electorate.

Think tanks and policy institutes, often funded by wealthy individuals and organizations, play a crucial role in shaping public policy. These entities produce research, propose policy solutions, and provide platforms for political discourse. While they contribute valuable expertise, their agendas are frequently aligned with the interests of their benefactors, further complicating the landscape of policy-making.

Despite these challenges, change in government is not impossible, but it often requires strategic navigation of the existing power structures. Successful leaders learn to work within the system, leveraging the expertise and institutional knowledge of the bureaucracy while building coalitions and consensus for their policy goals. Incremental change, though slower, can lead to significant shifts over time when pursued persistently and strategically.

For democracies to function effectively and reflect the will of the people, there must be a balance between continuity and change. While the permanence of the bureaucracy ensures stability, mechanisms for accountability and transparency are essential to prevent stagnation and undue influence by unelected power brokers. Strengthening democratic institutions, promoting transparency in campaign financing, and fostering a culture of accountability within the bureaucracy are crucial steps towards achieving this balance.

The interplay between elected officials, bureaucrats, and unseen power brokers in Western democracies highlights the complexities of governance and the challenges of enacting meaningful change. The permanence of the bureaucracy ensures essential continuity, yet this same stability necessitates a careful and strategic approach to policy-making. True democratic governance requires not only the election of representatives but also the cultivation of transparent and accountable institutions that can adapt to the evolving needs and aspirations of the people they serve.