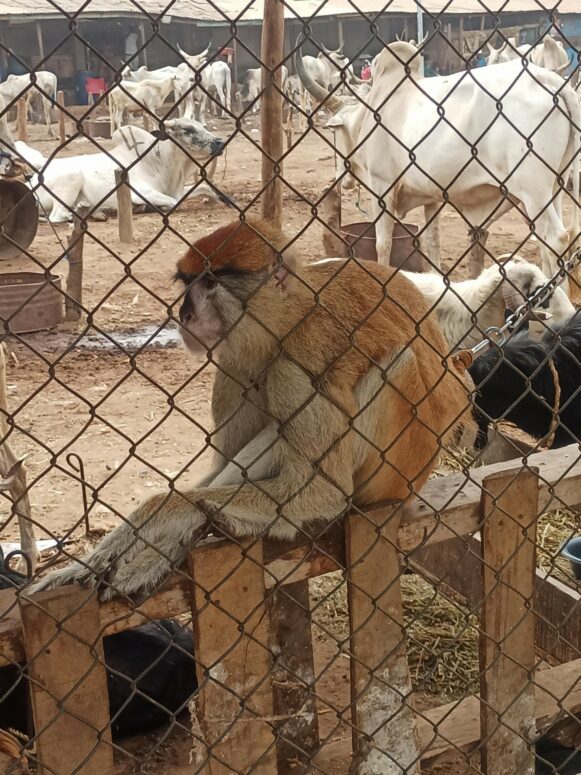

A light brown monkey, tethered to an enclosure, is up for sale for N80,000, about ($104), at a local livestock market in Ikorodu, Lagos state, Nigeria. The presence of the monkey at the market reflects the current threat faced by vanishing wildlife in the country. And here is how I found out about the animal.

I caught a rare glimpse. But it was enough to attract me to the animal. It felt like the sighting of a mythical creature in a vanishing rainforest. I hadn’t expected to see a chained monkey in a livestock market. But the sighting wasn’t a trick of vision.

We had driven by the Sabo livestock market in search of a goat for the New Year party when I saw the pale brown monkey against a wire fence, a chain around its waist. The salon car driver had gone ahead with some theatre because cars were honking wildly behind him on the busy road. Street traders had claimed a good portion of the road, leaving some room for motorists and pedestrians. But our driver finally found parking space in a gas station just up ahead the road, a walking distance from the market. Everyone got out hurriedly, grateful to flee from the heat in the car. There was no air-conditioning inside the cranky bright blue Toyota salon car.

My three friends walked toward the market, but I stayed back because I had devised a plan. I had questions about what the monkey was doing in a cattle and goat market. I believed the animal didn’t deserve to be kept among livestock and humans. How did it get there? Was there an illegal wildlife trade taking place in the market? Who was its owner? Was the animal for sale or a show monkey capable of excellent acrobatic falls? I had to find answers, and there was a way to do that.

Investigation

I approached the captured animal after my friends had walked deep into the market, searching for a cheap goat for the upcoming party. They didn’t care about animals captured from the wild against their will. They passed by the chained monkey, acting like nothing unusual was happening around the market. They had goat meat pepper soup on their minds. Party people had begun to gather somewhere in town.

I approached the monkey with a smile pasted on my face, my mobile phone in my hands, and with a bit of trepidation. Would I be allowed to take photographs or make a short video? A small shop was off the fence, and a woman sat there. After hearing her talk to some buyers, I spoke to her in the local Yoruba language. After seeking and getting permission, I began clicking away at the animal. There was a glint of surprise in the woman’s eyes.

The monkey just sat there looking at me, acting like it was no stranger to photographs and camera flashes. There was sadness in the way it looked. I moved closer and took another shot. But I was cautious around the animal, careful not to agitate the creature with the bright light from the phone.

“Who owns this monkey?” I asked the woman who sold groceries by the wire fence. “I love animals,” I added. I made another shot. But it wasn’t too good. My hands shook.

I learned that a man who sold the livestock by the fence owned the animal. I asked to see the man holding the monkey captive because I wanted to interview him, but he wasn’t anywhere close by. I took more photos of the monkey and soon made a 15-second video clip. The grocery woman was amazed by my actions towards an animal often overlooked. She asked why I had recorded the animal and if I wanted to buy the monkey. Or I had come for some cattle or goats? I would shoot another video when the monkey’s owner arrived on the scene. Of average height, black, with an unsmiling face, there was a wave of wild anger on his face. I resolved to speak to him, nonetheless.

“What’s happening here?” The unsmiling man asked. “What are you doing around my monkey?”

“The owner of the animal has come.” That was what the grocery woman announced.

I was glad to see him. I greeted the livestock trader, but I was met with hostility. The lines on his temple creased in anger, his pale eyes burning with disgust.

“Why are you taking a photograph of me?” The owner of the monkey charged in my direction. “Are you here to buy a goat, or are you here to take photos of a monkey?”

I had barely answered the questions when the man fired at me again, accusing me of taking unauthorized photos of him. “Take photos of the monkey, if you want, but not of me. I don’t like what you are doing.”

In truth, I hadn’t meant to take his photos, but he had strayed into my line of sight. And I had captured his face. But he wasn’t going to let me get away with it. Why was he afraid of a harmless photo? I couldn’t tell. The monkey’s master turned towards the woman I had spoken to when I arrived on the scene. He had a little altercation with her.

“You are my sister, and you sat there watching him. You don’t even know who he is!”

Who didn’t he think I was? A Police officer? A monkey rescuer?

“I can’t let a bad thing happen to you,” the woman began. “The man came to me at first, and he asked about the monkey and its owner. That was when I sent someone to look for you.”

But the monkey owner wanted more than the explanation he got. I feared he was going to smash my phone. He had raised his voice several octaves higher than his sister’s and mine. The heated exchange had attracted the men beside the kiosk, and they came into the scene one after another, asking the trader to calm down. But the man would have none of that. After the livestock owner raised his coarse voice, more people came into the picture. It took some time before he could listen to the explanation from one of the men who corroborated his sister. He was told I had asked questions and asked permission to photograph the monkey. And that had settled the brewing argument about my presence around his captive monkey.

But the man was still livid that I had taken a photo of him. I offered him my phone to search through, asking him to delete all images of himself. But he wouldn’t touch the device, walking toward his livestock instead. He kept repeating that he didn’t know who I was. There was a clear hint of fear in his voice. Was he aware that he was involved in the illegal wildlife trade?

I hurriedly scrolled through my photos and deleted the inadvertently taken images of the angry monkey owner. I gave my phone to the boy who had gone to fetch the livestock man, asking him to search if he would find a photograph of the man. The boy looked through my images and concluded that there was no photo of the monkey owner. The case was settled.

I made friendly overtures towards the monkey’s captor, explaining that I had come to town with friends to buy a goat. But he was tough to appease. It took some pleas from his sister before he mellowed down. To thank her for her patience and kind words, I purchased a small sachet of alcoholic bitters. I tore into it and drank. I offered my new friend a drink, but he didn’t accept the offer. But it was now safe to probe into the monkey and how it got to the market. I bought another drink while investigating the presence of the animal. I had become a temporary friend of the kiosk owner.

Arrival in the Livestock Market

“I brought it from the north when I went to buy cattle,” the trader said in response to a question about where the monkey came from. He didn’t say which part of the north, though. And I wanted to avoid pushing it, fully aware that this was a fractious fellow. He would have been suspicious had I moved for clarification. And then I learned that the animal was over two years old in the market.

The trader had loosened up at this time. And that was when I learned that the monkey’s favorite food was beans and eggs. And its favorite drink was Fanta! Such exotic food choices, I thought.

“Do you want to buy it?” The trader asked. “I see that you are in love with the animal.”

“How much would you sell it?”

“Eighty thousand Naira.”

“And what would you do with it if you bought it? Would you eat it?”

I informed him that I am no monkey eater, but I knew people who would love to care for the monkey and rehabilitate it before sending it back to its natural habitat.

Justifying Conservation

I said something in the words of Marilyn A. Norconk, Emeritus Professor, Kent State University: “The lucrative trade in African primates threatens their survival,” but my explanation sounded strange to those who were listening as I told them I would call the monkey Sabo if I had the chance to rescue it. I could see the strange looks on their faces. So, I began telling them a little about conservation, the extinction of animals, and the need for wildlife support.

My friends emerged from the belly of the market, one of them with a dwarf black-and-white goat in tow. I left the monkey and its owner, telling him my friends had gotten what they wanted, and I had to join them back to town.

“Goodbye, Sabo,” I said to the monkey, smiling. I imagined strange eyes staring at me as I walked away.

Who in the world is this guy? Why was he so bothered about a chained monkey? I expected they would ask themselves those questions. And they would have no problems providing the answers.

The higher monetary value placed on the monkey over an average size goat which can be purchased at N35,000 (the price my friends bought one), is a sign of the quick profit that can be made trading in illegal wildlife, to the detriment of the natural animal world. An illicit trader of wildlife stands to make N45,000 (56.3 percent) more over the price of a much larger goat were they to sell a smaller-sized monkey. Illegal wildlife trade has endangered Monkeys in most parts of the world.

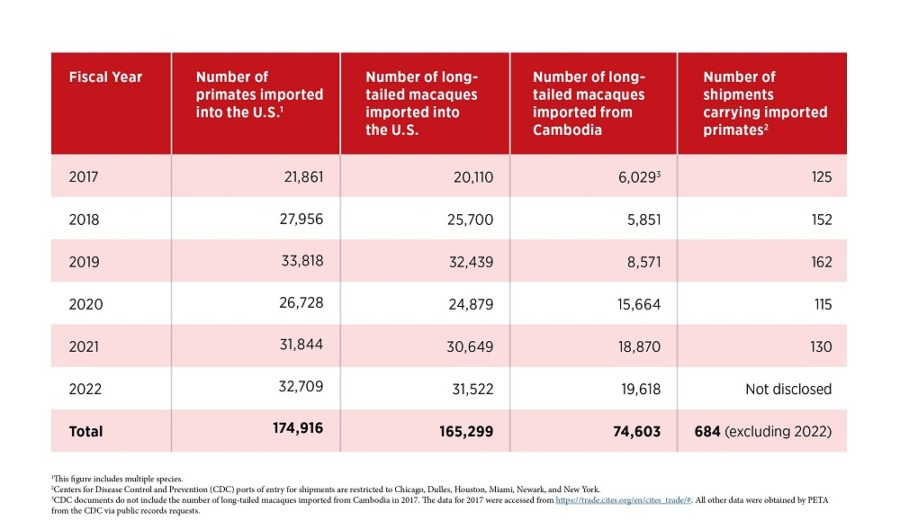

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) has produced a fact sheet on the illegal wildlife trade, and the data is frightening. Their report highlights the “role of US Experimenters in the illegal trade in wild-caught Monkeys.” PETA has noted: “US laboratories’ unceasing demand for monkeys to experiment on has driven two species to the brink of extinction, caused immeasurable suffering, failed to lead to meaningful improvements in human health, and likely encouraged the illegal trade in these animals.” From 2017-2022 alone, 174,916 primates were imported into the US. Within the same period, 165,299 long-tailed Macaques were imported into the US.

To See the Full PETA’s datasheet click here

Having seen “Sabo,” the monkey, I left the livestock market with a slim hope that the animal would witness a happy reunion with its colleagues in the wild. If not, the chained monkey may end up in someone’s cooking pot and become part of unreported illegal wildlife trade data. “The illegal trade, which Interpol now recognizes as ‘wildlife crime,’ is difficult to track but of deep concern since about 60% of primate species are now threatened with extinction,” Professor Norconk warns in her article in The Conversation.

In Nigeria, the threat faced by wildlife is graphic. To this end, groups and individuals are leading efforts to preserve the ecosystem. In Cross River state, Drill Ranch supports the protection of endangered Chimpanzees. The state also boasts of the Cross River National Park. There are Game Reserves in some parts of the country as well, the Yankari Game Reserve being one of them in Bauchi state in the country’s north.

The Nigeria Conservation Foundation (NCF) is one of the leading voices in the preservation of the environment. According to information on its website, www.ncfnigeria.org, the foundation has achieved some “milestones,” among other things. The following achievements are listed: “1984-Assisted to develop National Conservation Strategy, 1985-Supported the enactment of Endangered Species Decree, 1990-Established the Lekki Conservation Centre, 1992-Established the Hadejia-Nguru wetland Conservation project.”

Dr. Olaleru. Fatsuma is leading the cause for the preservation of Monkeys at the University of Lagos, where she is a lecturer and researcher at the Department of Zoology. She is actively protecting “indigenous mona-monkey populations,” a statement on the institution’s website says. “Olateru advocates for non-lethal human-mona monkey conflict resolutions in urban forest fragments of Lagos State and the species’ protection for eco-tourism.”

But more concrete steps are needed to ensure monkeys and other precious wildlife survive into the next century in the country. The monkey on sale at the Sabo livestock market indicates that people are trading in wild animals without fear of arrest from law enforcement officers, even when Nigeria boasts of the Endangered Species (Control of International Trade and Traffic) Act Decree No.11 of 1985. Animal Legal and Historical Centre at Michigan State University, www.animallaw.info, summarizes the animal protection act thus:

“the hunting or capture of or trade in animal species listed in the First Schedule to this Act is absolutely prohibited. Furthermore, no person shall hunt, capture, trade in, or otherwise deal with an animal species specified in the Second Schedule to this Act except if that person is in possession of a license issued under this Act. The Act also sets out the conditions of licenses and permits. The Minister may, by an order, publish in the Federal Gazette alter the list of animals specified in the First or Second Schedule to this Act by way of addition, substitution or deletion or otherwise. Penalties for violations are also provided.”

Unless animal protection laws are vigorously implemented, monkeys and other endangered animals will continue to be part of the illicit wildlife trade in Nigeria and elsewhere.